Nipah virus infection - Bangladesh - who.int

Situation at a glance

Nipah virus infection outbreaks are seasonal in Bangladesh, with cases usually occurring annually between December and May. Since the report of the first case in 2001, the number of yearly cases has ranged from zero to 67, though in the last five years, reported cases have been comparatively lower ranging from zero in 2016 to eight in 2019.

However, since 4 January 2023 and as of 13 February 2023, 11 cases (10 confirmed and one probable) including eight deaths (Case Fatality Rate (CFR) 73%) have been reported across two divisions in Bangladesh.

A multisectoral response has been implemented by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Bangladesh, including strengthened surveillance activities, case management, infection prevention and control, and implementation of risk communication campaigns.

WHO assesses the risk as high at the national level, moderate at the regional level, and low at the global level.

Description of the cases

Since 2001, Bangladesh has been reporting seasonal outbreaks of Nipah virus infection between December and May, corresponding with the harvesting season of date palm sap (DPS) occurring in the country from November to March. Reported cases ranged from zero (in 2002, 2006 and 2016) to 67 (in 2004). A lower number of reported cases was observed from 2016 following an extensive advocacy campaign against the consumption of raw date palm sap (Figure 1).

However, between 4 January to 13 February 2023, a total of 11 (ten confirmed and one probable) cases of Nipah virus infection including eight deaths (CFR 73%) were reported from seven districts across two divisions in Bangladesh. This is the highest number of cases since 2015 when 15 cases including 11 deaths were reported.

Ten of the 11 reported cases were laboratory confirmed, while samples could not be collected from one case before death and is therefore considered a probable case based on epidemiological linkage. Laboratory confirmation of Nipah virus infection was carried out through Real Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR) using samples from throat swabs and antibody detection via enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Confirmatory tests were done at the Institute of Epidemiology, Disease Control and Research (IEDCR) and International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh, (ICDDR, B) laboratories.

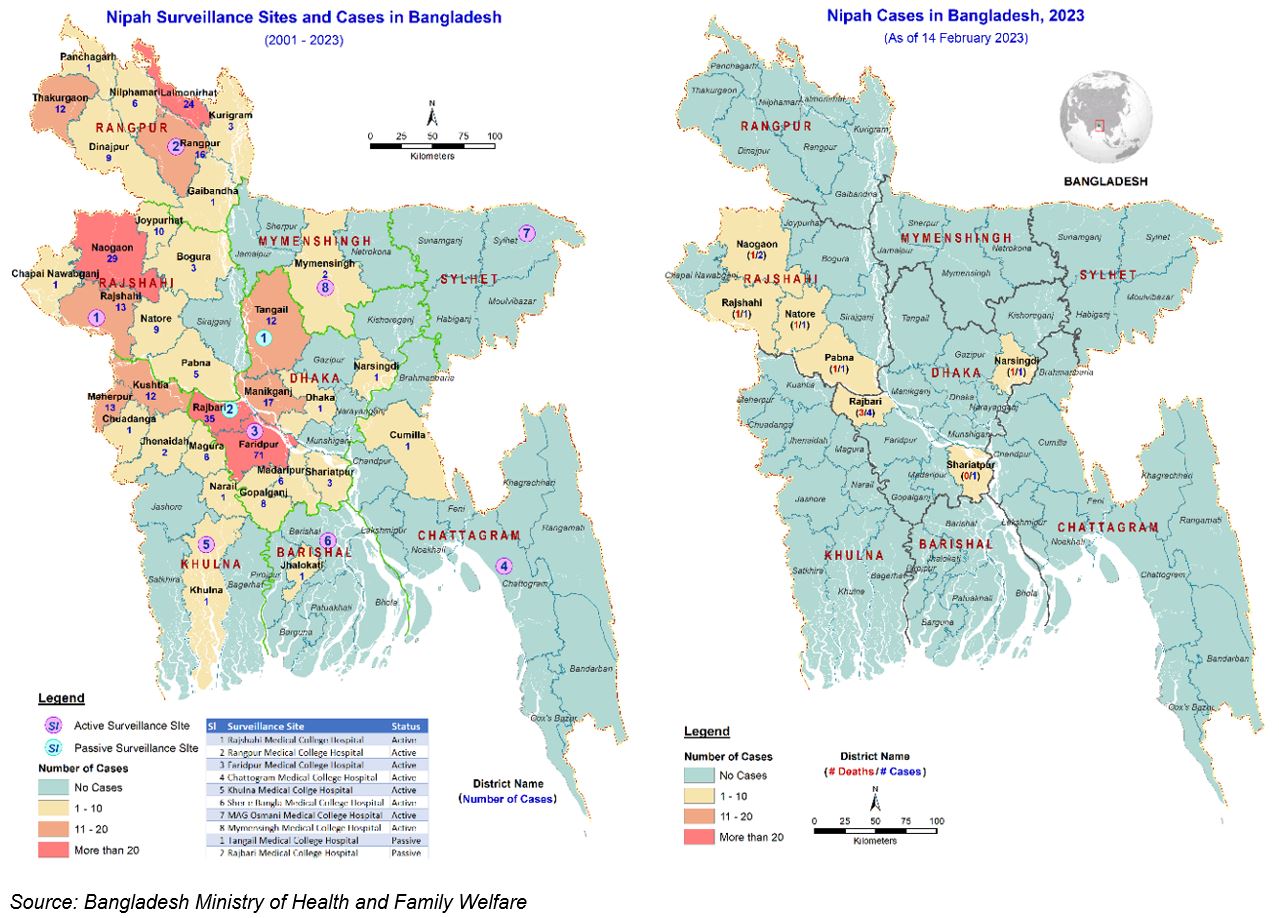

Six cases were reported from Dhaka Division including four deaths from the districts of Narsingdi (one case who died), Rajbari (four cases including three deaths) and Shariatpur (one case). Rajshahi Division reported five cases including four deaths from the districts of Naogaon (two cases including one death), Natore (one case who died), Pabna (one case who died), and Rajshahi (one case who died) (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Number of reported Nipah virus cases and deaths by year, 1 January 2001 – 13 February 2023, Bangladesh.

Figure 2. Distribution of Nipah Virus cases and surveillance sites (2001 – 2023) [Left] and Nipah cases in 2023 [Right].

Of the eleven cases reported, four were females and seven were males. The median age of cases is 16 years old, ranging from 15 days to 50 years. Of the 11 cases, ten had a history of consuming date palm sap while one case, a 15-day old infant is considered a secondary case.

Estimated incubation period of these cases ranged from 3 to 15 days with a median of 14 days. All of the 11 cases were hospitalized following the onset of symptoms.

A total of 310 contacts have been identified around the 11 cases and are monitored for 3 weeks from the last date of possible exposure.

Epidemiology of Nipah virus infection

Nipah virus infection is an emerging bat-borne zoonotic disease transmitted to humans through infected animals or contaminated food. It can also be transmitted directly from person to person through close contact with an infected person. Fruit bats or flying foxes (Pteropus species) are the natural hosts for Nipah virus.

The incubation period is believed to range from 4 to 14 days. However, an incubation period up to 45 days has been reported. Laboratory diagnosis of a patient with a clinical history of Nipah virus infection can be made during the acute and convalescent phases of the disease by using a combination of tests. The main tests used are RT-PCR from bodily fluids and antibody detection via ELISA.

Nipah virus infection in humans causes a range of clinical presentations, from asymptomatic infection (subclinical) to acute respiratory infection and fatal encephalitis. Infected people initially develop symptoms including fever, headaches, myalgia (muscle pain), vomiting, and sore throat. This can be followed by dizziness, drowsiness, altered consciousness, and neurological signs that indicate acute encephalitis. Some people can also experience atypical pneumonia and severe respiratory problems, including acute respiratory distress. Encephalitis and seizures occur in severe cases, progressing to coma within 24 to 48 hours. Most people who survive acute encephalitis make a full recovery, but long-term neurologic conditions have been reported in survivors. Approximately 20% of patients are left with residual neurological consequences such as seizure disorder and personality changes. A small number of people who recover subsequently relapse or develop delayed onset encephalitis.

The overall global case fatality rate is estimated at 40% to 75% depending on local capabilities for epidemiological surveillance and clinical management. Although antivirals are in development, there are no licensed vaccines or therapeutics available for the prevention or treatment of Nipah virus infection.

In the absence of a vaccine or licensed treatment available for Nipah virus infection, the only way to reduce or prevent infection in people is by raising awareness of the risk factors and educating about the measures persons can take to reduce exposure to the Nipah virus. Case management should focus on the delivery of supportive care measures to patients. Intensive supportive care is recommended to treat severe respiratory and neurologic complications.

Public health educational messages should focus on:

Reducing the risk of bat-to-human transmission: Efforts to prevent transmission should first focus on decreasing bat access to date palm sap and other fresh food products. Freshly collected date palm juice should be boiled, and fruits should be thoroughly washed and peeled before consumption. Fruits with signs of bat bites should be discarded. Areas where bats are known to roost should be avoided. The risk of international transmission via fruit or fruit products (such as raw date palm juice) contaminated with urine or saliva from infected fruit bats can be prevented by washing them thoroughly and peeling them before consumption.

Reducing the risk of animal-to-human transmission: Natural infection in domestic animals has been described in farming pigs, horses, goats, sheep, but also in dogs and cats. Gloves and other protective clothing should be worn while handling sick animals or their tissues, and during slaughtering and culling procedures. As much as possible, people should avoid being in contact with infected pigs. In endemic areas, when establishing new pig farms, considerations should be given to the presence of fruit bats in the area and in general, pig feed and pig sheds should be protected against bats when feasible. Samples taken from animals with suspected Nipah virus infection should be handled by trained staff working in suitably equipped laboratories. Nipah virus infection can be prevented by avoiding exposure to bats and sick animals in endemic areas, and by avoiding consuming fruits partially eaten by infected bats or drinking raw date palm sap/toddy/juice.

Reducing the risk of human-to-human transmission: Close unprotected physical contact with Nipah virus-infected people should be avoided. Regular hand washing should be carried out after caring for or visiting sick people. Health care workers caring for patients with suspected or confirmed infection, or handling their specimens, should implement standard infection control precautions at all times. As human-to-human transmission has been reported among caregivers including family members and in health-care settings, contact and droplet precautions should be used in addition to standard precautions. Airborne precautions may be required in certain circumstances.

Comments

Post a Comment