Mucormycosis: the black fungus hitting Covid-19 patients - BBC News

Fungal infections can be devastating. And one in particular – mucormycosis – is adding to the burden of suffering in a country already in a deep Covid-19 crisis. We've seen reports from India of infections with mucormycosis, often termed "black fungus", in patients with Covid-19, or who are recovering from the coronavirus.

As of March this year 41 cases of Covid-19-associated mucormycosis had been documented around the world, with 70% in India. Reports suggest the number of cases is now much higher, which is unsurprising given the current wave of Covid-19 infections in India.

But what is mucormycosis, and how is it linked with Covid-19?

What is mucormycosis?

Mucormycosis, formerly known as zygomycosis, is the disease caused by the many fungi that belong to the fungal family "Mucorales". Fungi in this family are usually found in the environment – in soil, for example – and are often associated with decaying organic material such as fruit and vegetables.

The member of this family most often responsible for infections in humans is called Rhizopus oryzae. In India though, another family member called Apophysomyces, found in tropical and subtropical climates, is also common.

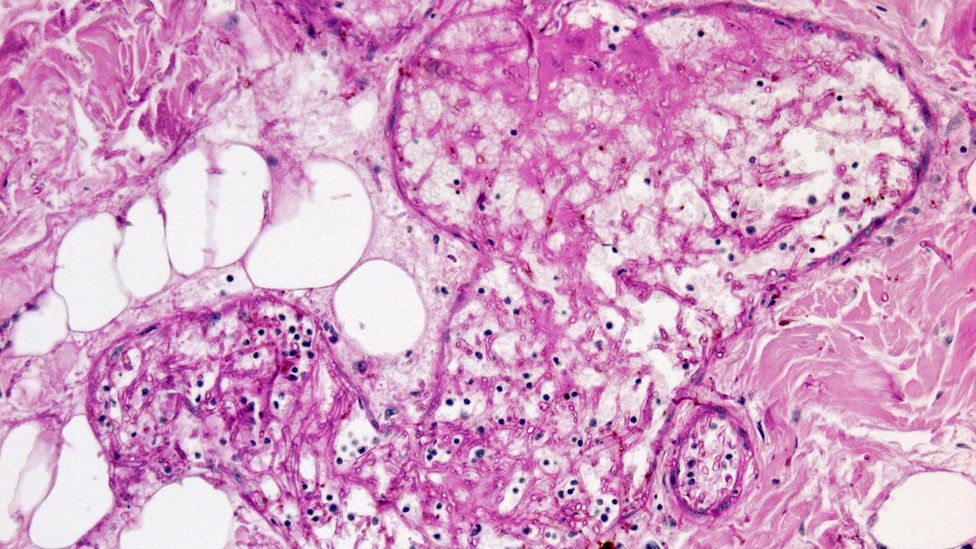

The fungi that cause mucormycosis are found normally in soil and on rotting organic material but can infect humans when they get a chance (Credit: Science Photo Library)

In the laboratory, these fungi grow rapidly and have a black-brown fuzzy appearance.

Those that cause human disease grow well at body temperature and in acidic environments – the kind seen when tissue is dead, dying or associated with uncontrolled diabetes.

How do you get mucormycosis?

Fungi in the Mucorales family are considered opportunistic, meaning they usually infect people with an impaired immune system, or with damaged tissue. Use of drugs which suppress the immune system such as corticosteroids can lead to impaired immune function, as can a range of other immunocompromising conditions, like cancer or transplants. Damaged tissue can occur after trauma or surgery.

There are three ways humans can contract mucormycosis – by inhaling spores, by swallowing spores in food or medicines, or when spores contaminate wounds.

Inhalation is the most common. We actually breathe in the spores of many fungi every day. But our immune systems and lungs, if healthy, generally prevent them from causing an infection.

You might also be interested in:

- What we know and don't know about Covid-19

- The people with high Covid-19 resistance

- How Covid-19 might mutate in the future

When our lungs are damaged and our immune systems suppressed, such as is the case in patients being treated for severe Covid-19, these spores can grow in our airways or sinuses, and invade our bodies' tissues.

Mucormycosis can manifest in the lungs, but the nose and sinuses are the most common site of mucormycosis infection. From there it can spread to the eyes, potentially causing blindness, or the brain, causing headaches or seizures.

Crematoriums in New Delhi have been struggling to cope with the deaths caused by Covid-19 and secondary infections like mucormycosis are adding to the problems (Credit: Reuters)

It can also affect the skin. Life-threatening wound infections have been seen after injuries sustained during natural disasters or on battle fields where wounds have been contaminated by soil and water.

In the environment

There have been very few mucormycosis infections associated with Covid-19 in countries other than India. So why is the situation there so different?

Before the pandemic, mucormycosis was already far more common in India than in any other country. It affects an estimated 14 in every 100,000 people in India compared to 0.06 per 100,000 in Australia, for example.

Globally, outbreaks of mucormycosis have occurred due to contaminated products such as hospital linens, medications and packaged foods. But the widespread nature of the reports of mucormycosis in India suggests it's not coming from a single contaminated source.

Mucorales can be found in soil, rotting food, bird and animal excretions, water and air around construction sites, and moist environments.

Although never compared, it may be that Australia has a lower environmental burden of Mucorales than in India.

But there could be another factor at play in India – diabetes.

When diabetes is poorly controlled, blood sugar is high and the tissues become relatively acidic – a good environment for Mucorales fungi to grow. This was identified as a risk for mucormycosis in India (where diabetes is increasingly prevalent and often uncontrolled) and worldwide well before the Covid-19 pandemic. Of all mucormycosis cases published in scientific journals globally between 2000-2017, diabetes was seen in 40% of cases.

A recent summary of Covid-19-associated mucormycosis showed 94% of patients had diabetes, and it was poorly controlled in 67% of cases.

A perfect storm

People with diabetes and obesity tend to develop more severe Covid-19 infections. This means they're more likely to receive corticosteroids, which are frequently used to treat Covid-19. But the corticosteroids – along with diabetes – increase the risk of mucormycosis.

Meanwhile, the virus that causes Covid-19 can damage airway tissue and blood vessels, which could also increase susceptibility to fungal infection.

Mucormycosis can be life threatening in patients already struggling against a disease such as Covid-19 (Credit: Money Sharma/AFP/Getty Images)

So damage to tissue and blood vessels from Covid-19 infection, treatment with corticosteroids, high background rates of diabetes in the population most severely affected by the coronavirus, and, importantly, more widespread exposure to the fungus in the environment are all likely to be playing a part in the situation we're seeing with mucormycosis in India.

Treatment challenges

In many Western countries, we've seen increased cases of another fungal infection, Aspergillosis, in patients who had severe Covid-19 infections, needed intensive care management and received corticosteroids. This fungus is also found in the environment but belongs to a different family.

As Aspergillosis is the most common opportunistic fungus globally, and we have tests to rapidly diagnose this infection. But this is not the case with mucormycosis.

For the many patients affected with mucormyosis, the outcome is poor. About half of patients affected will die and many will sustain permanent damage to their health.

Diagnosis and intervention as early as possible is important. This includes control of blood sugar, urgent removal of dead tissue, and antifungal drug treatment.

But unfortunately, many infections will be diagnosed late and access to treatment is limited. This was the case in India prior to Covid-19 and the current demands on the health system will only make things worse.

Controlling these fungal infections will require increased awareness, better tests to diagnose them early, along with a focus on controlling diabetes and using corticosteroids wisely. Patients will need access to timely surgery and antifungal treatment. But there also needs to be more research into prevention of these infections.

* Monica Slavin is an expert in lung infections at the Royal Melbourne Hospital and head of the department of infectious diseases at the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre in Melbourne, Australia.

* Karin Thursky is a professor of microbiology at The Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity, in Melbourne, Australia and director of the National Centre for Antimicrobial Stewardship.

This article originally appeared on The Conversation, and is republished under a Creative Commons licence.

--

Join one million Future fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter or Instagram.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called "The Essential List". A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife, and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

Comments

Post a Comment